History of the Romanised Writing System for the Vietnamese Language: Formation and Popularisation Periods

Thanh Tran, PhD

(Source: Commemorative Book to Mark 50 Years of Vietnamese Refugee Settlement in Australia – VCA-NSW 2025)

In 2025, overseas Vietnamese will commemorate half a century of settling in their second homeland. Throughout their journey of building lives in new homelands and integrating with the local people, the Vietnamese community has continuously engaged in activities to preserve their unique cultural identity. Maintaining the Vietnamese language, whether spoken or written (chữ Quốc Ngữ), is one of the focal points of these activities.

Litterally, Quốc Ngữ means the national language. This confusing term is short for “chữ Quốc Ngữ” which practically means the romanised script of the Vietnamese language. Before the advent of chữ Quốc Ngữ, Chữ Nôm and Classical Chinese were used as scripts to record the Vietnamese language. With its origins borrowed from Classical Chinese, Chữ Nôm found it difficult to develop into a widespread script. Quốc Ngữ, although created to serve the missionary work of Western missionaries, gradually became the script that all Vietnamese people use today and is the nation’s unified writing system.

When did Quốc Ngữ emerge? Who were the pioneers in its creation? Where was the cradle of Quốc Ngữ? This article briefly presents the formation and development of chữ Quốc Ngữ to answer these questions.

I. Quốc ngữ and the Jesuit Missionaries

I.1 Origin of the Term “Quốc Ngữ”

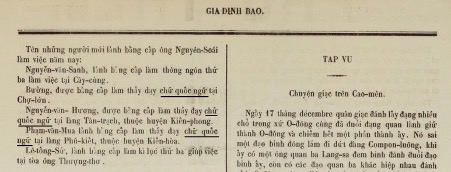

The first question that should be raised is when and by whom the term “Quốc Ngữ” (or more precisely “chữ Quốc Ngữ”) was created. According to (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 295), the earliest document containing this term that the author finds is page 2 of Gia Định Báo, issue 1, 1867.

Phạm conjectures that famous Vietnamese figures like Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký (1837–1898) and Paulus Huỳnh Tịnh Của (1830–1908) were important voices in choosing the name “chữ Quốc Ngữ”.

I.2 A Misconception

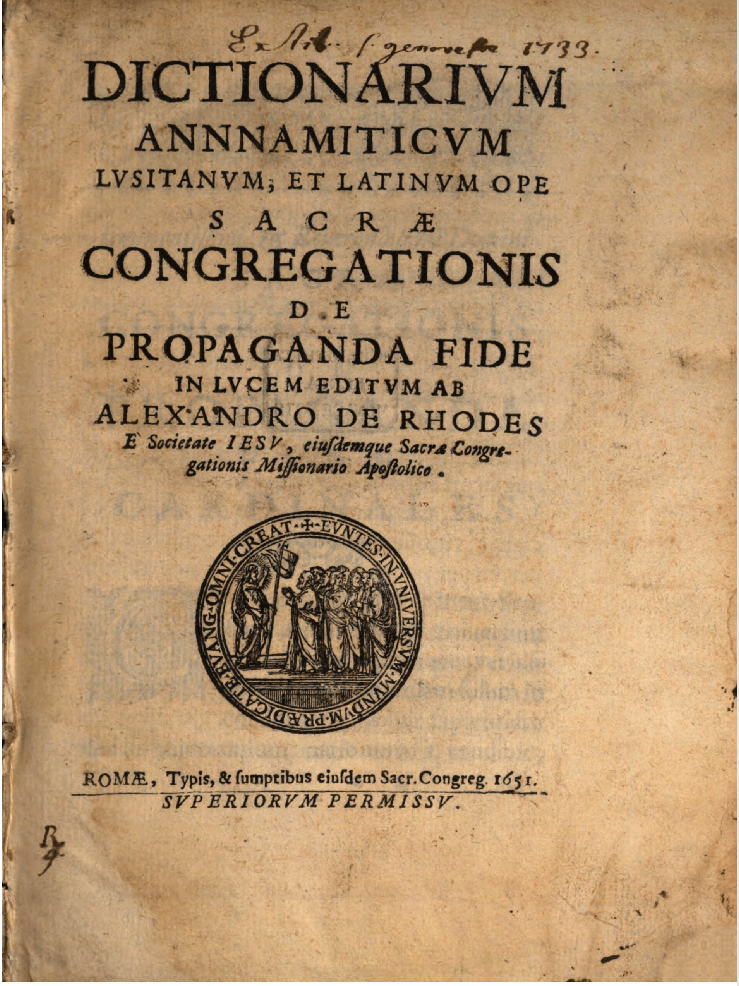

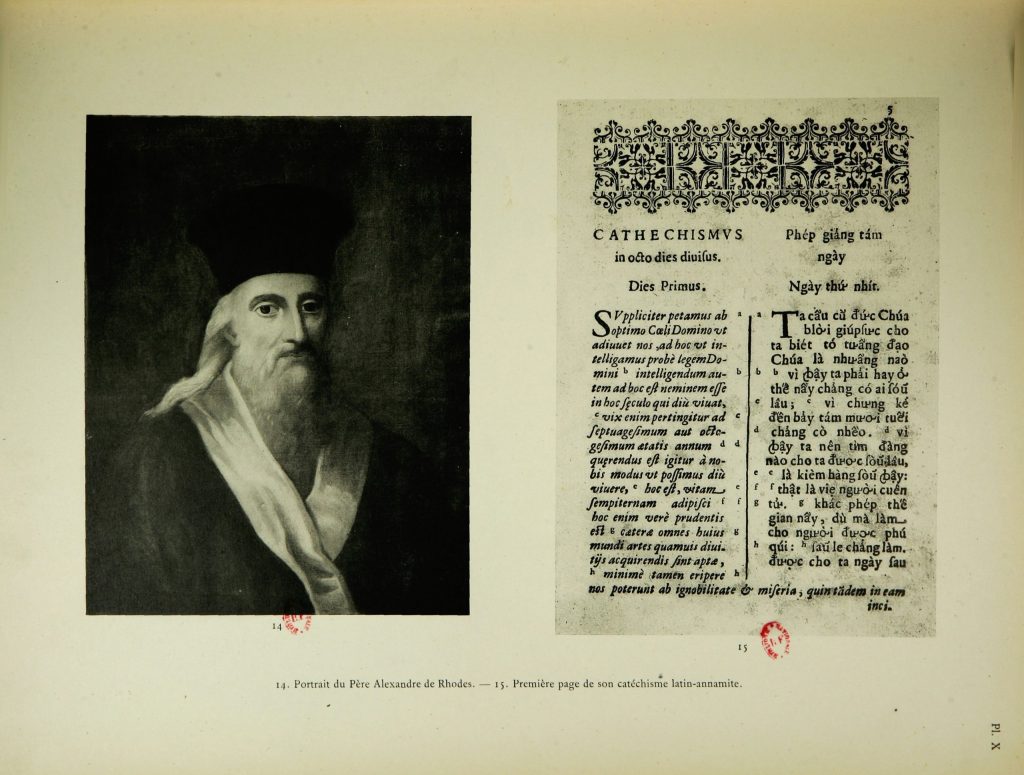

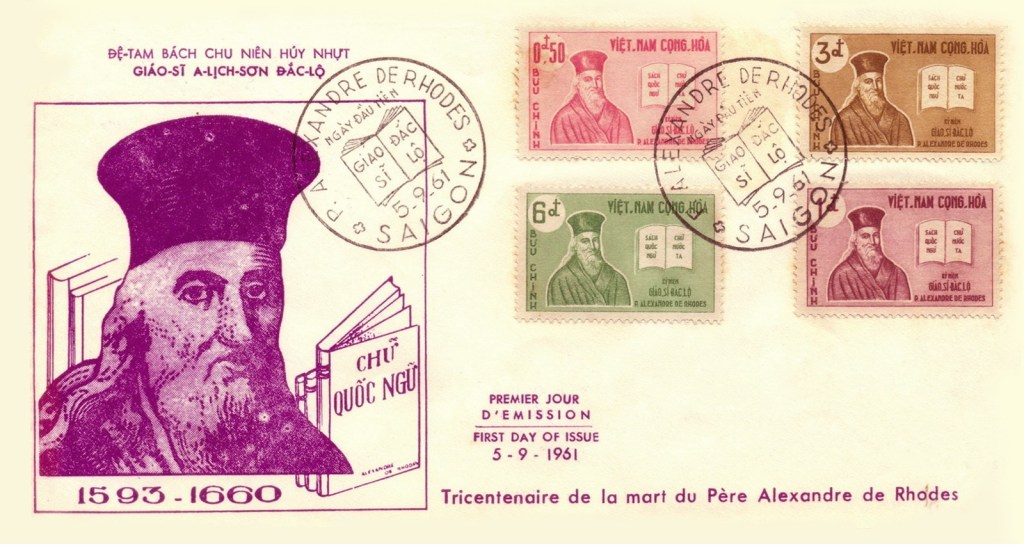

In 1651, the Dictionarium Annamiticum, Lusitanum et Latinum (Annamese–Portuguese–Latin Dictionary) and Phép giảng tám ngày cho kẻ muốn chịu phép rửa tội mà vào đạo thánh Đức Chúa Trời (Eight-Day Catechism for Those Who Wish to Receive Baptism and Enter the Holy Religion of God) were published in Rome. The author of these two publications was clearly stated on the cover as Alexandre de Rhodes. These were the first two publications in Quốc Ngữ, making them important milestones in understanding the history of this script. Therefore, when Quốc Ngữ became widely popular throughout Vietnam in the early 20th century, gradually replacing Classical Chinese and Nôm, Father Alexandre de Rhodes was credited with originating the Latin script for recording the Vietnamese language. It’s also possible that for political reasons, the French colonial government in Indochina at the time attributed primary credit to him for creating Quốc Ngữ, considering him its father.

(Source: Vietnamese Heritage Museum)

Few Vietnamese people currently over the age of 60, who lived and grew up south of the Bến Hải River, have not heard the name Alexandre de Rhodes (who many are familiar with the Sino-Vietnamese transcription A-lịch-sơn Đắc Lộ or simply Cha Đắc Lộ). Before 1975, his name was given to a street in front of the Independence Palace (now the Reunification Palace) in Saigon. In 1985, the street was renamed Thái Văn Lung, but in 1995, the street was once again given the name Alexandre de Rhodes.

In 1941, a commemorative stele of Father de Rhodes was erected in Hanoi near the entrance of Ngoc Son Temple (on Hoan Kiem Lake). In 1957, the stele was removed and went missing from 1984, only to be recovered in 1992. Since 1995, the stele has been kept in the garden area of the National Library in Hanoi.

From the latter half of the 20th century, some researchers disagreed with the view that de Rhodes was the father of Quốc Ngữ, though they still acknowledged his significant pioneering contribution. This research began with Vietnamese priests trained in Europe, such as Nguyễn Khắc Xuyên (NGUYỄN Khắc Xuyên, 1959, 1960), Thanh Lãng (THANH LÃNG, 1961), Đỗ Quang Chính (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972), and researchers Lê Ngọc Trụ (LÊ Ngọc Trụ, 1961) and Võ Long Tê (VÕ Long Tê, 1965).

Following them was the DEA thesis (Diplôme d’Études Approfondies) by French researcher Roland Jacques, presented in 1995 at INALCO [1] (JACQUES Roland, 1995). He rewrote this thesis and published it as a bilingual English-French book (JACQUES Roland, 2002).

Most recently is the 2018 doctoral dissertation by Phạm Thị Kiều Ly at Sorbonne Nouvelle University, France (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018). This dissertation was rewritten and published as a book in French and translated into Vietnamese (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024).

These new studies demonstrate that Alexandre de Rhodes’ dictionary was the result of the collaborative efforts of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries: Francisco de Pina, António de Fontes, Gaspar do Amaral, and António Barbosa, along with Alexandre de Rhodes’ direct editorial work.

To better understand the history of the formation of Quốc Ngữ, we need to understand the political context of Vietnam when Christian missionaries arrived.

I.3 Political and Geographical Context of Vietnam in the 17th Century and the Presence of Jesuit

I.3.1 Đại Việt’s Contact with the West

The political situation in Vietnam in the 17th century was very complex. At that time, the country nominally belonged to the Later Lê Dynasty, with the national name Đại Việt. However, the Lê kings held no real power. The area south of the Gianh River (Quảng Bình Province) was called Đàng Trong (Inner Realm), built by Nguyễn Hoàng and ruled by the Nguyễn Lords from 1600. The area north of the Gianh River was called Đàng Ngoài (Outer Realm), ruled by the Trịnh Lords. Additionally, the Cao Bằng area was held by descendants of Mạc Đăng Dung; Western missionaries referred to this area as Đàng Trên (Upper Realm).

The first missionaries who came to Đại Việt were mostly Jesuit priests from Portugal. This was a consequence of the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494 between the two powerful empires of the 15th century: Spain and Portugal. This treaty divided the world into two halves along a meridian in the Atlantic Ocean, situated between the Cape Verde Islands (west of Africa, then under Portuguese control) and the islands newly discovered by Christopher Columbus (under Spanish control, modern-day Cuba and Hispaniola). Newly discovered lands to the east of this meridian would belong to Portugal, while those to the west would belong to Spain. This explains the presence of the Portuguese and the absence of the Spanish in Đại Việt.

These missionaries called Đàng Trong “Cocicina” and Đàng Ngoài “Tunquin” or “Tonquim”. In the work published in 1631, “Relatione della nvova missione delli PP. della Compagnie di Giesu, al regno della Cocincina”, which was translated into French by Bonifacy (BONIFACY, 1931), Cristoforo Borri explains the origin of the word Cocincina as follows. The Japanese at the time called Annam Coci. When they introduced the Portuguese merchants to the region, these merchants also used the word Coci, but added Cina to it, implying the Coci land of China, to distinguish it from the place name Cocin in India. Similarly, due to the way the Japanese pronounced the word Đông Kinh (meaning Đông Đô, the capital of Đại Việt), the Portuguese called the capital of Đại Việt Tunquin.

Léonard Aurousseau explained more clearly the origin of the word “Coci” in his article Sur le nom de Cochinchine (About the Name Cochinchine) (AUROUSSEAU Léonard, 1924, pages 574–575). According to Aurousseau, the Chinese called Đại Việt “Kiao-tche kouo” (Giao Chỉ Quốc), which was pronounced “Coci” or “Cauci” by the Japanese. When they introduced Portuguese merchants to the region, these merchants also used the word “Coci”, but added “Cina” to it, implying the Coci land of China, to distinguish it from the place name “Cocin” in India. Thus, initially, “Cocicina” was a name referring to the entire country of Đại Việt, while “Tunquin” was Đông Kinh or Đông Đô, the capital of Đại Việt. When missionaries arrived in Đàng Trong in 1615, to distinguish it from Đàng Ngoài, they called Đàng Trong “Cocicina” and Đàng Ngoài “Tunquin”. See also (PHAN Khoang, 1969, pages 543–544). These two place names had many different spellings, including Cochinchine and Tonkin.

Later, the French also used the terms Cochinchine to refer to Southern Vietnam (Nam Kỳ) and Tonkin to refer to Northern Vietnam (Bắc Kỳ). However, there was a difference. “Tunquin” during the time the Jesuit missionaries arrived in Đại Việt in the 17th century referred to the land north of the Gianh River (excluding Cao Bằng, which belonged to the Mạc Dynasty), while “Cocicina” stretched from south of the Gianh River to Phú Yên. The land south of Phú Yên, from Nha Trang to Hà Tiên, then belonged to Champa and Cambodia. In contrast, French Cochinchine extended from Bình Thuận to Hà Tiên, and Tonkin was the land north of Hải Vân Pass, up to the border with the Qing Dynasty. The land between Tonkin and Cochinchine belonged to the Annam Imperial Court of the Nguyễn kings.

I.3.2 Missionary Linguistics

When Western missionaries arrived in a new land, to serve their missionary work, they had to learn the local language. To aid in learning this local language, they sought to transcribe the local language using Latin characters, a language most missionaries were fluent in. The next important step was to compile dictionaries and grammar books of that language, following the patterns of Latin grammar. This was a common trend in missionary linguistics. A typical example is in Japan.

Arriving in Japan in the mid-16th century (1549), Jesuit missionary François Xavier initiated the use of Latin script to transliterate the Japanese language. In doing so, he and his fellow missionaries learned Japanese and used it in their missionary work. Many works compiling grammar books, dictionaries, and catechisms were completed. Notable examples include the Dictionarium Latino Lusitanicum ac Iaponicum (Latin, Portuguese, Japanese Dictionary) published in 1595 by several European missionaries and fellow brothers, Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam (1603–1604, anonymous author), and Arte da lingoa de Iapam (Japanese Grammar) by João Rodriguez [2] published between 1604–1608; see (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018, page 45). The aforementioned Jesuit missionaries made significant progress in Romanizing the Japanese writing system.

However, in 1612, during the Tokugawa Shogunate, a policy prohibiting Christianity was enacted. Jesuit missionaries were extensively expelled, forcing them to seek refuge in Macao (old documents referred to it as Áo Môn, based on the Chinese transliteration). They had a great influence on the Jesuit missionaries assigned to Đại Việt [3].

I.4 Jesuit Missionaries Arriving in Đại Việt

In the early 17th century, the Jesuit mission for Southeast Asia was established, headquartered in Macao, under the jurisdiction of the Japanese Province. According to Đỗ Quang Chính (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 22), from 1615 to 1788, 145 Jesuit priests of 17 different nationalities came to Vietnam to evangelize. The majority of these were Portuguese (74 people), followed by Italian (30), German (10), Japanese (8), French (5), Spanish (4), Chinese (2), Macanese (2), Polish (2), and a few other countries, one person from each.

The following missionaries are more or less related to the creation of chữ Quốc Ngữ.

I.4.1 The First Three Missionaries to Đàng Trong in 1615

The first three Jesuit missionaries to Đàng Trong were Francesco Buzomi (Italian), Diego Carvalho (Portuguese), and António Dias (Portuguese) [4]. They boarded a Portuguese merchant ship from Macao on 6th January 1615, arrived at Cửa Hàn (Da Nang) on 18th January 1615, and then went to Faifo (Hải Phố or currently Hội An).

I.4.2 Francisco de Pina (1585–1625) Arrived in Đàng Trong in 1617

Two years after the three missionaries Buzomi, Carvalho, and Dias arrived in Hội An, in 1617, Francisco de Pina (Portuguese) also came to this coastal town. His name is also written as Francisco da Pina. Among the missionaries who came to Đại Việt during this period, F. de Pina is considered the first to be fluent in Vietnamese (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 22).

Francisco de Pina was born in 1585 in Guarda, a city in the mountainous region of Portugal famous for its magnificent churches. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1605, studying at St. Paul’s College in Macao from 1611 to 1617. There he met João Rodriguez, who had recently compiled the Japanese grammar book (see section I.3.2).

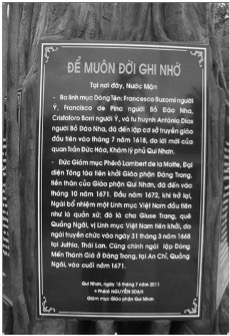

According to Đỗ Quang Chính (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 22) [5], in 1618, Francisco de Pina moved to Nước Mặn (Bình Định) [6] with Father Buzomi and Borri. Two years later, he returned to Hội An, and then in 1623, he settled in Kẻ Chàm [7]. On December 15, 1625, Francisco de Pina and a Vietnamese man rowed out to a Portuguese ship anchored off the coast of Hội An to receive liturgical items. On their way back, they were caught in a storm, their boat capsized, and he died. His body was recovered and buried in Hội An, but no trace of it can be found today. Currently, there are three unmarked ancient tombs within the grounds of Phước Kiều Church (in Thanh Chiêm, Điện Bàn, Quảng Nam). People suspect (without supporting evidence) that one of these tombs belongs to Francisco de Pina [8].

I.4.3 Cristoforo Borri (1583–1632) Arrived in Đàng Trong in 1618

Cristoforo Borri (some documents write Christoforo Borri) arrived in Hội An one year after F. de Pina, in 1618. He was a missionary as well as an Italian mathematician and astronomer, born in Milan, who joined the Society of Jesus in 1601. After arriving in Hội An, he followed Fathers Buzomi and de Pina to establish a mission in Nước Mặn; see note [6]. He lived there for three years, becoming fluent in Vietnamese. In 1621, he left Đàng Trong and returned to Portugal to teach mathematics and astronomy at the Colégio das Artes (College of Arts) in Coimbra and the Colégio de Santo Antão (College of Saint Anthony) in Lisbon. His Italian book Relatione della nvova missione delli PP. della Compagnie di Giesu, al regno della Cocincina is an important work for understanding the history of chữ Quốc Ngữ; see section II.1.1.

I.4.4 Pedro Marques (1576–1657) First Arrived in Đàng Trong in 1618

According to the Diccionario Histórico de la Compañía de Jesús: Biográfico-Temático (Historical Dictionary of the Society of Jesus: Biographical Thematic), there were two priests with the same name, Pedro Marques, who lived during the same period and are often confused by researchers.

On pages 2512 and 2513 of this dictionary (O’NEILL Charles E. & DOMÍNGUEZ Joaquín M., 2001), the two men are distinguished as Pedro Marques and Pedro Marques (junior) or Pedro Marques-Ogi. Pedro Marques (1576–1657) was born in Portugal and died in Japan while Pedro Marques-Ogi (1612–1670) was born in Nagasaki, Japan, and died off the coast of Hainam Island due to a shipwreck.

Meanwhile, Đỗ Quang Chính (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, p. 22) asserts that Pedro Marques was born in 1575 in Japan to a Portuguese father and Japanese mother, and died in 1670 due to a shipwreck near Hainan Island.

Both aforementioned documents agree that Pedro Marques (senior) arrived in Cochinchina (Đàng Trong) in 1618. Therefore, we believe that the Father Pedro Marques referred to by Father Đỗ Quang Chính is the senior priest and that this author has mistaken the biography of this priest. This individual served as the Superior of the Jesuits in Hoi An in 1620—a landmark year that will be discussed in the following section.

I.4.5 Alexandre de Rhodes, (1593–1660) Arrived in Đàng Trong in December 1624

Alexandre de Rhodes was born in 1593 [9] in Avignon, a Papal territory purchased by the Holy See of Rome, now part of France. He entered the Society of Jesus in Rome in 1612.

He arrived in Hội An at the end of 1624, then lived and studied Vietnamese with Francisco de Pina in Thanh Chiêm. According to (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 2011), the Superior sent him to Đàng Trong to learn Vietnamese with de Pina and then sent him to Đàng Ngoài via Macao (because at that time Đàng Trong and Đàng Ngoài were hostile to each other).

In 1626, he left Đàng Trong for Macao and then arrived in Thanh Hoá (Đàng Ngoài) in 1627. There, he was highly regarded by Lord Trịnh Tráng, who allowed him to evangelise for the first year. Later, accused of being a spy for the Nguyễn Lords, he was expelled in 1630. Leaving Đại Việt, he went to Macao, returning to Đàng Trong from 1640 to 1645; during that period, he was expelled several times.

At the end of 1645, he sailed back to Rome. In 1655, the Superior sent him to Ispahan (also known as Esfahan or Isfahan), then the capital of Persia (now Iran), more than 400km south of Tehran. He died on November 5, 1660, and was buried there.

I.4.6 António de Fontes (1569–?) Arrived in Đàng Trong in December 1624

Father António de Fontes was born in 1569 in Lisbon (year of death unknown). He arrived in Đàng Trong at the end of 1624, residing at the Jesuit residence in Kẻ Chàm (Thanh Chiêm) with Alexandre de Rhodes, and learned Vietnamese from Francisco de Pina. He served the mission in Đàng Trong from 1624 to 1631, then went to Đàng Ngoài until 1648. In 1626, he wrote an annual report in Portuguese to send to the Jesuit Superior General in Rome. This report contained many chữ Quốc Ngữ words, which will be discussed later (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, pages 34–37; PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 115). He played a role in spreading chữ Quốc Ngữ from Đàng Trong to Đàng Ngoài.

I.4.7 Gaspar d’Amaral or Gaspar do Amaral (1592–1645) Arrived in Đàng Ngoài in October 1629

The dictionary (O’NEILL Charles E. & DOMÍNGUEZ Joaquín M. (Eds), 2001, page 96) states that Father Gaspar do Amaral was born in 1594 in Portugal and died due to a shipwreck off Hainan Island on February 26, 1646. He was sent by the Jesuits to Macao in 1623. From Macao, he went to Đàng Ngoài several times, first in October 1629. He contributed to compiling the Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary (Diccionário anamita-português-latim), in addition to a handwritten document in Portuguese from 1632, which contained many chữ Quốc Ngữ words (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972). This dictionary is now lost. However, Father Đắc Lộ’s dictionary (see section I.2 above and II.1.2 below) states that he inherited from that work.

I.4.8 António Barbosa (1594–1647) Arrived in Đàng Ngoài in 1636

According to (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 67), António Barbosa was born in 1594 in Portugal, arrived in Đàng Ngoài at the end of April 1636, and returned to Macao in May 1642 due to health reasons. He died in 1647 while en route to Goa (India). He compiled the Portuguese–Vietnamese dictionary (Diccionário português-anamita) between 1636–1642 while in Đàng Ngoài. In his dictionary (see section I.2 above and II.1.2 below), Father Đắc Lộ also mentioned inheriting results from this dictionary. António Barbosa’s dictionary is now lost.

II. Documents Related to Chữ Quốc Ngữ

Researchers of the history of chữ Quốc Ngữ rely on documents, both published and handwritten, to determine the time of its emergence.

II.1 Published Works

II.1.1 Cristoforo Borri’s Italian Book

Perhaps the first publication related to Quốc Ngữ is the book written by Cristoforo Borri in Italian and published in Rome in 1631: “Relatione della nvova missione delli PP. della Compagnie di Giesu, al regno della Cocincina.” The book was translated into many other languages: French, English, German, Dutch, Latin. There are two French translations, one by Antoine de la Croix from 1631 (de LACROIX Antoine, 1631) and one by Bonifacy published in Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué (Đô Thành Hiếu Cổ) in 1931, issues 3-4 (BONIFACY, 1931). In 1811, John Pinkerton translated this work into English (PINKERTON John, 1811).

In this book, Borri recorded some Quốc Ngữ words. Due to the scope of this article, we will only quote a few words here:

Anam (An Nam), Tunchim (Đông Kinh), Ainam (Hải Nam), Quignin (Qui Nhơn), scin mocaij (xin một cái – ask for one thing).

Although the book was published in 1631, because the author Cristoforo Borri left Đàng Trong in 1621 to return to Portugal (see biography in section I.4.3 above), according to Đỗ Quang Chính, it can be understood that the Quốc Ngữ words in this book existed from 1621 or earlier.

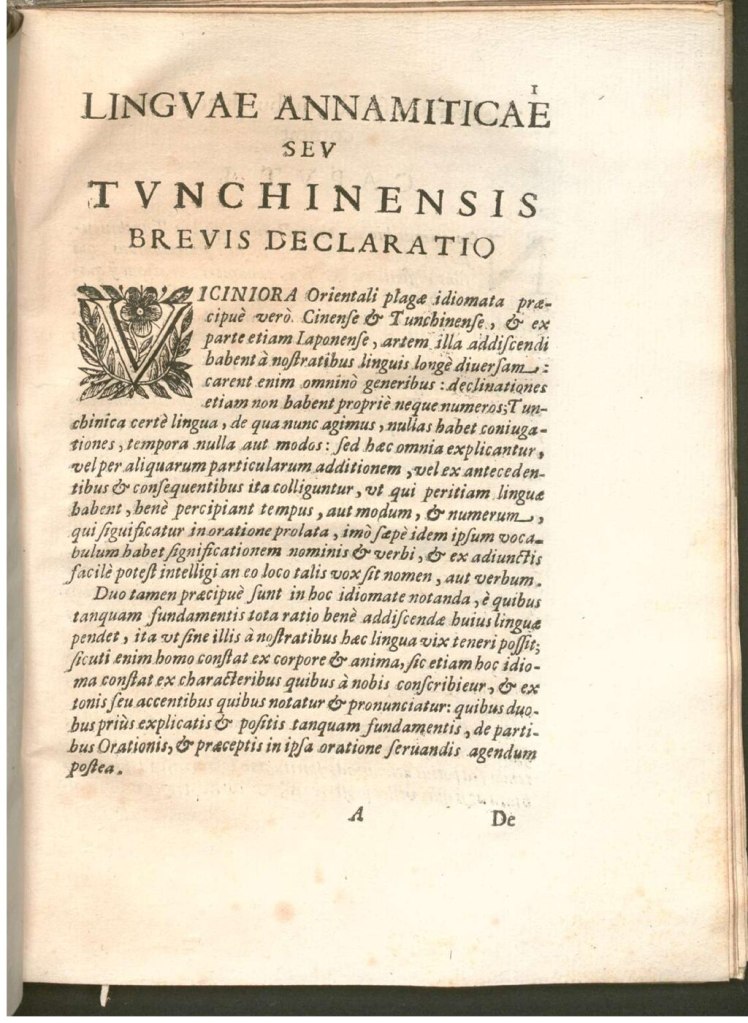

II.1.2 Alexandre de Rhodes’ Dictionary and Book

Two other important publications are by Alexandre de Rhodes, as mentioned in section I.2: the Dictionarium Annamiticum, Lusitanum et Latinum and the Phép giảng tám ngày, printed in 1651. The final part of the dictionary is a Vietnamese grammar book in Latin, “Linguae Annamiticae seu Tunchinensis brevis declaratio” (A brief description of the Annamese or Tonkinese language). Thus, both important parts of missionary linguistics, dictionary and grammar, were printed in the same book.

In 1991, priests Thanh Lãng, Hoàng Xuân Việt, and Đỗ Quang Chính translated the entire book into Vietnamese (THANH LÃNG et al., 1991). Recently, Sister Maria Thérèse Bùi Thị Minh Thúy added several documents and data to this translation (BÙI Thị Minh Thùy, 2021). Andrew Gaudio translated the grammar section into English (GAUDIO Andrew, 2019).

II.1.3 Taberd’s and Aubaret’s Dictionaries

It took almost 200 years after Alexandre de Rhodes published his book, when France began to intervene in Vietnam (1838), for two other dictionaries in Quốc Ngữ to appear: the Latin–Vietnamese dictionary (Dictionnarium annamitico-latinum) and the Vietnamese–Latin dictionary (Dictionnarium latino-annamiticum) by Taberd. In 1861, Louis-Gabriel-Gadéric Aubaret published Vocabulaire français-annamite et annamite-français, précédé d’un traité des particules annamites (French-Annamese and Annamese-French Vocabulary, preceded by a treatise on Annamese particles).

II.2 Handwritten Documents

Since the 1960s, researchers have discovered many handwritten documents related to Quốc Ngữ in archives, which appeared many years before the publications of Cristoforo Borri and Alexandre de Rhodes. Researchers use these documents to determine the birth of Quốc Ngữ and find answers to the question of who created this script.

First, the discoveries of Đỗ Quang Chính must be mentioned. His work Lịch sử chữ quốc ngữ (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972) (History of Quoc Ngu) discussed the documents he found in archives and libraries in Rome, Madrid, Lisbon, Paris, Lyon, and Avignon. After Đỗ Quang Chính came Roland Jacques when he discovered Francisco de Pina’s report (JACQUES Roland, 1995). Most recently are the discoveries of Phạm Thị Kiều Ly (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018).

II.2.1 Đỗ Quang Chính’s Discoveries

Based on the handwritten documents found in the archives, Đỗ Quang Chính divided the formation of chữ Quốc Ngữ into two phases:

II.2.1.a Phase One: From 1620 to 1626

Đỗ Quang Chính primarily relied on two handwritten annual reports sent to the Jesuit Superior General in Rome.

- First is the report by Father João Roiz (see note [2]), written in Macao on November 20, 1621, in Portuguese.

- The second report is by Father Gaspar Luis, written in Macao on December 12, 1621, in Latin. According to Léopold Cadière (CADIÈRE Léopold, 1931), the letter was dated December 17, 1621.

These two reports describe missionary activities in 1620 in Đàng Trong, with two important main points:

- The missionaries in Hội An had compiled a handwritten catechism in Chữ Nôm. This book is now lost. Because both reports recorded some Quốc Ngữ words, Đỗ Quang Chính hypothesised that the aforementioned catechism was also compiled in Quốc Ngữ but has been lost.

The four Jesuit missionaries present in Hội An in 1620 were responsible for compiling the aforementioned catechism. They were:

- Pedro Marques (see biography in section I.4.4), superior of the Jesuit missionaries there;

- Joseph, Japanese, active in Đàng Trong from 1617 to 1639. The book (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 23) states that Joseph’s Japanese name could not be found. According to Fukuda Yasuo in his article Người Nhật có liên quan sâu sắc tới quá trình thiết lập phiên âm tiếng Việt bằng ký tự Latin (The Japanese were deeply involved in the romanisation of the Vietnamese language) (FUKUDA Yasuo, 2016), between 1615 and 1621, four Japanese missionaries came to Đàng Trong: Miguel Maki, José Tsuchimochi, Paulo Saito, and Romão Nish. Therefore, we hypothesise that the Brother Joseph mentioned by Đỗ Quang Chính is José Tsuchimoch;

- Paulo Saito, Japanese, lived in Đàng Trong from 1616 to 1627;

- Francisco de Pina (see biography in section I.4.2 above).

Among these four missionaries, Francisco de Pina was the most fluent in Vietnamese.

- Another important detail in João Roiz’s report is that in addition to teaching Vietnamese to Jesuit missionaries, Francisco de Pina completed a vocabulary book in 1619.

Therefore, Đỗ Quang Chính believed that Francisco de Pina was the first to create Quốc Ngữ, starting from 1620.

Đỗ Quang Chính also listed the handwritten documents of Alexandre de Rhodes (1625), Gaspar Luis (1626), Antonio de Fontes (1626), and Francesco Buzomi (1626) in his book.

Here are some examples of Quốc Ngữ recorded in the aforementioned handwritten documents and in Cristoforo Borri’s book (de LACROIX Antoine, 1631).

Unsai, onsaij (ông sãi – Buddhist monk), ungue, omgne (ông nghè – laureate), ondelim (ông đề lĩnh – high-ranking official), Nuocman, Nuoecman (Nước Mặn, see note [6]), Cacciam, Cacham (Kẻ Chàm or Thanh Chiêm, see note [7]), Quignin, Quinhin (Qui Nhơn).

Muon bau dau christiam chiam: Muốn vào đạo Christiang chăng. (Do you want to convert to Christianity?).

Although the spelling was not consistent in the above documents, the general observation is that these words were written with two or more syllables combined and without diacritics, unlike current Quốc Ngữ, which is monosyllabic and has diacritics. This is why Đỗ Quang Chính considered the period from 1620 to 1626 as phase one. However, Đỗ Quang Chính also noted that monosyllabic writing with diacritics began to appear in two reports by Antonio de Fontes and Francesco Buzomi in 1626. For example:

Dinh Cham (Dinh Chàm), xán tí (thượng đế – God), thien chu (thiên chủ, thiên chúa, God), ngaoc huan (ngọc hoàng – Jade Emperor).

II.2.1.b Phase Two: From 1631 to 1648

Đỗ Quang Chính identified this phase based on the following documents:

- Handwritten documents by de Rhodes from 1631, 1636, 1644, 1647;

- Handwritten documents in Portuguese by Gaspar d’Amaral from 1632 and 1637.

He made the following observations:

- In 1631, de Rhodes’ Quốc Ngữ writing was still inferior to Francesco Buzomi’s in 1626. The 1644 document was better, but then in 1647, he wrote Quốc Ngữ similarly to the 1636 period.

- In 1632, Gaspar d’Amaral wrote Quốc Ngữ better than Alexandre de Rhodes, even though his total time in Đại Việt (Đàng Ngoài) was 28 and a half months, while Alexandre de Rhodes stayed in both Đàng Trong and Đàng Ngoài for 57 months. Đỗ Quang Chính listed many Quốc Ngữ words in G. d’Amaral’s two handwritten documents, many of which are written like we write today: Kẻ chợ (market town), đàng ngoài (Outer Realm), Thanh đô Vương (Thanh Đô King), etc.

- Book (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 66) also quoted ancient documents stating that Gaspar d’Amaral had compiled the Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary (Diccionário anamita-português-latim) before Alexandre de Rhodes compiled his dictionary. De Rhodes clearly wrote that he used d’Amaral’s dictionary (see section I.4.7) and António Barbosa’s Diccionário português-anamita to compile his own (see section I.4.8).

- According to (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, page 67), before his book was published, Vietnamese and foreign researchers of Quốc Ngữ history had overemphasised Alexandre de Rhodes’ contributions. A few researchers expressed reservations (perhaps Đỗ Quang Chính was referring to Nguyễn Khắc Xuyên and Thanh Lãng), but due to a lack of clear documentation, they did not dare to assert who was truly better than de Rhodes. Thanks to his discovery of d’Amaral’s documents, he was able to assert this.

- Chapter 3 of the book (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972) provides many details about de Rhodes learning Vietnamese, initially with Francisco de Pina and a 13-year-old Vietnamese boy. Đỗ Quang Chính concluded that Francisco de Pina was the first person to use Latin script to transcribe Vietnamese sounds.

II.2.2 Roland Jacques’ Discoveries

In 1995, Roland Jacques found a report by Francisco de Pina, written in 1622, in the Biblioteca da Ajuda library; see (JACQUES Roland, 1995, 1998, 2002) and (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018, page 197). In this report, F. de Pina stated that he was compiling a grammar book. Along with the fact that he had compiled a vocabulary book (see section II.2.1.a above), this important detail confirms Đỗ Quang Chính’s earlier conclusion that Francisco de Pina was indeed the first to create Quốc Ngữ.

II.2.3 Phạm Thị Kiều Ly’s Discoveries

II.2.3.a Four Handwritten Documents Before 1621

Phạm Thị Kiều Ly’s doctoral dissertation presented at Sorbonne Nouvelle University (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018) presented four handwritten documents older than the 1621 documents mentioned by Đỗ Quang Chính and Léopold Cadière. Like the previous reports, the documents listed here were compiled in Macao, based on reports from missionaries in Đàng Trong, to report to the Superior General in Rome on the progress of evangelization in An Nam.

- A 1617 document in Portuguese (anonymous author). The Quốc Ngữ word recorded in this document is Chuua, which was the title for the ruler in Đàng Trong at that time (Chúa Nguyễn – Nguyễn Lord).

- A 1618 document in Italian (anonymous author). The influence of Italian is clearly visible in the transcription of local place names mentioned in this document. For example, the capital of Quảng Nam Dinh, Kẻ Chàm or Thanh Chiêm (see note [7]), is transcribed as Cacian according to Italian pronunciation [10].

- A 1619 document by João Roiz (see note [2]) written in Portuguese. The influence of Portuguese is again evident in this document. The place name Kẻ Chàm here is recorded as Cacham according to Portuguese pronunciation. In addition, there are Nuocmả and Nuocman to transcribe Nước Mặn (see note [6]).

- A 1620 document signed by João Roiz, transcribed and translated into English by Jason Wilber in his Master of Arts thesis (WILBER M. Jason, 2014). This document states that in 1619, the first vocabulary book was compiled by Jesuit missionaries. However, it does not specify which language was used in this vocabulary book. According to Phạm Thị Kiều Ly, there is reason to believe that this book was written in Quốc Ngữ and translated into Portuguese or Latin. In Father Francisco de Pina’s report around 1622–1623, he stated that he had previously compiled a vocabulary book. Thus, there is reason to believe that the aforementioned vocabulary book belongs to de Pina.

These new discoveries show that Quốc Ngữ may have been created as early as 1617, not 1621 as previously concluded by Đỗ Quang Chính. This proves that Quốc Ngữ was created long before Alexandre de Rhodes arrived in Đại Việt (1624) and provides further grounds to believe that Francisco de Pina was the pioneer.

II.2.3.b In-depth Analysis of Grammar and Phonetics

In addition to the four documents listed above (among many others), the majority of Phạm Thị Kiều Ly’s dissertation meticulously analyzes grammatical and phonological issues in the formation of Quốc Ngữ. That issue is beyond the scope of this article. However, we can note from the dissertation that the pronunciation and alphabet of Portuguese and Italian had a great influence on the Quốc Ngữ alphabet.

One example is the sound nh in Vietnamese, which is written as nh in Portuguese reports but as gn in Italian reports (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018, page 176). The Portuguese transcription prevailed in this case [11].

Another example, in the introduction to the Vietnamese edition, the author states that in the summer of 2019 (after the dissertation had been submitted), she discovered some 16th-century Italian documents with the two sounds ơ and ư as in chữ Quốc Ngữ, appearing for the first time in António de Fontes’ report in 1631 (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 13). This opened up a new research direction for her regarding the origin of these two sounds ơ and ư.

III. Silent Contributions During the Formation of Quốc Ngữ

III.1 Role of Vietnamese People

The role of Vietnamese people in the early stages of chữ Quốc Ngữ’s creation cannot be denied. Đỗ Quang Chính dedicated an entire chapter to this contribution (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, Chapter 4), in which he mentioned the handwritten documents of Igesico Văn Tín and Bento Thiện. But before that, the author mentioned a teenager who helped A. de Rhodes learn Vietnamese.

III.1.1 Raphaël Rhodes

In his book (de RHODES Alexandre, 1653, page 73), Alexandre de Rhodes stated that a Vietnamese teenager helped him learn to pronounce the different tones of Vietnamese in three weeks, even though the two did not understand each other’s language. According to Đỗ Quang Chính (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, pages 79–80), this teenager was baptized by Alexandre de Rhodes with the Christian name Raphaël. Later, he became Brother Raphaël Rhodes (out of affection for de Rhodes, he asked to bear the same surname).

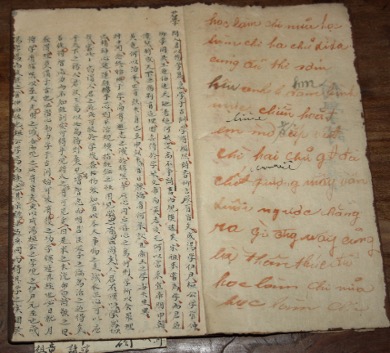

III.1.2 Igesico Văn Tín

The letter of Brother Igesico Văn Tín, written in 1659, currently preserved in the Jesuit Archives in Rome, is two pages long (17×25 cm, slightly smaller than A4), addressed to Father Filippo de Marini, a Jesuit missionary who came to Đàng Ngoài in 1647 and was expelled in 1658 (VÕ Long Tê, 1965). The content of the letter inquired about and reported on the situation of the faithful in Đàng Ngoài.

III.1.3 Bento Thiện

The letter of Brother Bento Thiện in 1659 was also sent to Father Filippo de Marini, two pages long (21×31 cm), describing the situation of missionaries and the faithful. This letter was discovered and published by Hoàng Xuân Hãn in 1959 (HOÀNG Xuân Hãn, 1959).

A long article on the history, geography, and customs of our country was handwritten by Bento Thiện in 1659, sent to Filippo de Marini for him to write the book Historia et relatione del Tunchino in 1665 (HOÀNG Xuân Hãn, 1959, page 109). Đỗ Quang Chính republished the entire document to show that Bento Thiện had considerable knowledge of Vietnamese literature and society (ĐỖ Quang Chính, 1972, pages 108–129).

III.1.4 Filippe Bỉnh

Because Đỗ Quang Chính limited his research to the period from 1620 to 1659, he did not mention the documents of Vietnamese priest Filippe Bỉnh (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 271; THANH LÃNG, 1961, page 29). He was born in 1759 in Hải Dương and ordained a priest in 1793. For 37 years, from 1796 to 1833, he and his fellow brothers collected and copied dictionaries and works on Vietnamese history and the lives of saints.

Phạm Thị Kiều Ly states that the Vatican Library contains 41 volumes of handwritten documents (each volume 500 to 700 pages) related to Đàng Ngoài and Đàng Trong, 33 of which were compiled by Filippe Bỉnh. The majority of these documents are written in chữ Quốc Ngữ, with the rest in Portuguese and Classical Chinese. These important documents show the development of chữ Quốc Ngữ in the 19th century.

III.2 Role of Japanese People

The Japanese Province of the Society of Jesus, formed in the mid-16th century, became the largest Jesuit province in Asia in the early 17th century, including China and Vietnam, with its headquarters in Macao. However, in 1612, the Tokugawa Shogunate issued an edict prohibiting Christianity, and by 1614, Western missionaries were expelled. Seventy-three Jesuit missionaries fled to Macao. From then on, they and the Jesuit missionaries already residing in Macao shifted their missionary work to Đại Việt (Đàng Trong), including Francisco de Pina, as mentioned above. He had learned from Joam Rodriguez how to transliterate Japanese using Latin script.

Francisco de Pina, like many other missionaries, set foot in Đại Việt via Hội An. Here, there was a Japanese quarter granted autonomy by the Nguyễn Lords. Many sources provide different figures for the number of Japanese living there in the early 17th century, but at least 200–300 people (FUKUDA Yasuo, 2016), among whom were some Japanese missionaries fleeing persecution.

It is noteworthy that from 1615 to 1621, 14 missionaries arrived in Đàng Trong. The majority were Portuguese missionaries (7 individuals), followed by Japanese (4 individuals), including Miguel Maki, José Tsuchimochi, Paulo Saito, and Romão Nishi. These Japanese missionaries were highly proficient in Latin.

According to Fukuda, these Japanese missionaries and collaborators, along with Japanese residents in Hội An, served as bridges for Western missionaries to communicate with Vietnamese people using Vietnamese, Classical Chinese, Japanese, and Latin. Fukuda speculates that when Francisco de Pina initially learned Vietnamese, he relied on Vietnamese individuals familiar with Classical Chinese to translate Vietnamese words into Classical Chinese. Then, he would ask a Japanese missionary fluent in Classical Chinese and Latin to translate these words into Latin, from which Francisco de Pina would then translate them into Portuguese. Therefore, according to Fukuda, the support of the Japanese contributed to the birth of Quốc Ngữ.

IV. Quốc Ngữ Script During the French Colonial Period

IV.1 Quốc Ngữ Script Spreads Beyond the Church

IV.1.1 In Cochinchina (Southern Vietnam)

Before the French occupied the three eastern provinces of Cochinchina (namely Biên Hòa, Gia Định, and Định Tường) in 1858, Quốc Ngữ was exclusively used within the church. Western missionaries used it to learn Vietnamese, and Vietnamese missionaries used it to communicate with each other and with their Western counterparts. When the French established schools in Cochinchina, the teaching of Quốc Ngữ began.

According to the Revue Maritime et Coloniale (Journal of Maritime and Colonial Affairs) of the French Ministry of Marine and Colonies (1865), the Collège des interprètes français (French Interpreters’ School) was founded to teach Quốc Ngữ to the French (at that time, Quốc Ngữ was referred to as the Vietnamese language written in Latin characters). The journal does not specify the founding year of the school. Page 304 also reported on a decree signed on 21st September 1861, establishing the École de l’Évêque d’Adran (School of Bishop of Adran, named after the title of Bishop Pigneau de Béhaine, also known as Bá Đa Lộc) [12]. By 1864, another decree opened primary schools in many locations, with teaching staff who had studied at the two aforementioned schools. From then on, Quốc Ngữ began to spread to the general public, including non-Catholics.

IV.1.2 In Annam (Central Vietnam) and Tonkin (Northern Vietnam)

In Central and Northern Vietnam, from 1898, Quốc Ngữ became a mandatory part of the Hương examination [13] (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 320) (see Figure 9). Not long before, the French established the Hậu Bổ school (School of Administration) to teach French and Quốc Ngữ to future administrative officials (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 319). After the last Hương examinations in Tonkin in 1915 and Annam in 1919, the old Sino-Vietnamese scholarship and examination system officially came to an end.

IV.2 The Role of the Press

IV.2.1 Gia Định Báo and the Role of Trương Vĩnh Ký

The birth of Gia Định Báo, the first periodical in Quốc Ngữ, marked a new phase in the development of this writing system [14]. Pages 400–402 of (NGUYỄN Văn Trung, 2014) indicate that there are still many uncertainties regarding the founding and cessation years of this magazine, although there is strong evidence to suggest that the first issue was published in April 1865. According to Phạm Thị Kiều Ly, the first issue was published on 15th April 1865, in Saigon (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, page 323). Initially, it was published monthly, later becoming weekly. The first Editor in Chief of the magazine was Ernest Potteaux, followed by Trương Vĩnh Ký (also known as Petrus Ký), Diệp Văn Cương, and Bonet.

Initially, Gia Định Báo had only two main sections: public affairs and miscellaneous affairs. The public affairs section published decrees and edicts of the colonial government in Cochinchina. The miscellaneous affairs section was dedicated to news on economics, religion, and other topics. From September 1869, when Trương Vĩnh Ký was appointed chief editor, he added a cultural section to discuss literature and ethics. Along with Paulus Huỳnh Tịnh Của and Trương Minh Ký, he gradually transformed the magazine, popularising the use of Quốc Ngữ by promoting new knowledge through articles on Vietnamese literary works, poetry, and proverbs.

It is also worth mentioning that Petrus Ký and Paulus Của transcribed Vietnamese fairy tales and legends into Quốc Ngữ and translated them into French. In addition, Petrus Ký published books on ethics, geography, and history for students. The publication of dictionaries and grammar books was also a significant contribution by these two individuals to the dissemination of Quốc Ngữ. In 1883, Trương Vĩnh Ký published Grammaire de la Langue Annamite (Vietnamese Grammar), and in 1887, he published Vocabulaire Annamite–Français (Vietnamese–French Vocabulary). In 1895, Huỳnh Tịnh Của published Dictionnaire annamite (Đại Nam quấc âm tự vị). As mentioned in the Missionary Linguistics section in the first part of this series of articles (History of the Romanised Writing System for the Vietnamese Language: Formation Period), the compilation of dictionaries and grammar books were important contributions to the romanisation of the Vietnamese language and the popularisation of this writing system [15].

IV.2.1 Other Newspapers

IV.2.1.a In Cochinchina (Southern Vietnam)

Thông Khoá Loại Trình was a type of textbook compiled by Trương Vĩnh Ký. Several other Quốc Ngữ newspapers were also founded by Vietnamese individuals, including: Nhựt Trình Nam Kỳ (1897), Phan Yên Báo (1898), Nông Cổ Mín Đàm (1901), and Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn (1907). Kim Vân Kiều Truyện, Vietnamese most celebrated piece of literature in form of a long poem written by renowned poet Nguyễn Du, and Lục Vân Tiên, an epic poem written by Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, were also transcribed by Trương Vĩnh Ký from Nôm script into Quốc Ngữ.

IV.2.1.b In Annam (Central Vietnam) and Tonkin (Northern Vietnam)

Đăng Cổ Tùng Báo (1907) was the first private newspaper in Quốc Ngữ (and Chinese characters) in Tonkin. This newspaper was closely associated with the Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục movement. Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh played a crucial role in popularising Quốc Ngữ through the publication of Đông Dương Tạp Chí. Phạm Quỳnh, Phan Kế Bính, Nguyễn Văn Tố, and Phạm Duy Tốn were prominent scholars who contributed to this newspaper. Additionally, Phạm Quỳnh and Nguyễn Bá Trác used Nam Phong Tạp Chí to disseminate literature and science.

V. Why Did Romanised Japanese Script (Romaji) Fail to Become Widespread?

Among the three Asian languages, Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese, Japanese posed the fewest difficulties for Jesuit missionaries. This was because its tonal system was simpler compared to Vietnamese and Chinese (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018, page 43). As early as the mid-16th century, between 1564 and 1567, grammar books were already being compiled. By 1585, a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary was compiled. Due to these being handwritten documents with many errors from careless copying, François Xavier decided to print and publish the prepared books.

From then on, anonymous works like Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam (Japanese Vocabulary) and João Rodriguez’s Arte da lingoa de Iapam (Japanese Grammar) were published; see (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018, page 45). The aforementioned Jesuit missionaries made clear progress in romanising the Japanese writing system (Romaji).

However, as we know, this writing system is not the common writing system for the entire nation of Japan today. Why is that? One important reason is likely the lack of an administrative decision from the central government (in Vietnam’s case, this was the French colonial administration). Could another reason be that during Japan’s modernisation period, it lacked a significant linguist to help improve this writing system? Regarding Vietnam and the development of the national romanised script, Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký stands as this pivotal historical figure.

VI. Where Is the Cradle of Quốc Ngữ?

The final question we want to address is where Quốc Ngữ was initially created. Throughout the article on the formation period of Quốc Ngữ (also in this book), three locations are mentioned most frequently: Hội An, Thanh Chiêm, and Nước Mặn. Currently, there are many differing opinions.

Some researchers believe that Hội An and Thanh Chiêm are where Quốc Ngữ was created. The reasoning is that Hội An was the location of the first residence (church) established in 1615 (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024), and Thanh Chiêm was the administrative centre of Quảng Nam at that time, a place that attracted many intellectuals who could help missionaries learn Vietnamese (HUỲNH Văn Mỹ & BẢO Trung, 2014). The Vietnamese program of VOA (Voice of America) even produced a documentary to confirm that Thanh Chiêm was the birthplace of Quốc Ngữ (VOA Tiếng Việt, 2017).

The article on Tuổi Trẻ Online cited above also presents the opinion of some researchers who believe that Nước Mặn is where Quốc Ngữ originated. The article quotes Mr. Trần Đình Trắc (a former lecturer at Qui Nhơn Pedagogical University before 1975) who stated that in 1972, he and several intellectuals in Bình Định submitted a proposal to the Advisory Council on Education of the Government of the Republic of Vietnam to build a monument and erect a statue of Alexandre de Rhodes to mark Nước Mặn’s role in the birth of Quốc Ngữ. Due to social instability caused by the war, the project was not carried out. Currently, there is a stele in Nước Mặn recording this historical detail (VÕ Đình Đệ, 2022).

In an attempt to find the answer, we have relied on ancient documents discovered by Đỗ Quang Chính and Phạm Thị Kiều Ly to establish the following chronology:

| Year | Events Related to Missionaries | Events Related to Quốc Ngữ Script |

| 1615 | Francesco Buzomi, Diego Carvalho, and António Dias arrived in Cochinchina, building a church (residence) in Hội An. | |

| 1617 | Francisco de Pina arrived in Hội An. | The first Quốc Ngữ word recorded in the oldest text found to date. This document was written in Portuguese and contained only one word: “Chuua.” |

| 1618 | Francisco de Pina arrived in Nước Mặn. A residence (church) was established there. | |

| 1619–1620 | F. de Pina completed compiling the first dictionary. | |

| 1620 | F. de Pina returned to Hội An. | |

| 1620–1623 | F. de Pina began compiling a grammar book for the language of Cochinchina (it is unclear if he completed it). | |

| 1623 | F. de Pina arrived in Thanh Chiêm, staying at Phước Kiều church. | |

| 1624 | Alexandre de Rhodes arrived in Đại Việt (Cochinchina) and studied Vietnamese with F. de Pina. | |

| 1625 | F. de Pina passed away. |

Based on the chronology, if we consider the completion of a dictionary as the birth of Quốc Ngữ, then that period would be from 1619 to 1620. Francisco de Pina was living in Nước Mặn during this time. Therefore, we lean towards the hypothesis that Nước Mặn is the cradle of Quốc Ngữ. After that, it was likely Hội An (when F. de Pina compiled the grammar book), followed by Thanh Chiêm.

VII. Conclusion

Quốc Ngữ is the romanised script for the Vietnamese language. This achievement is the result of many individuals, beginning with the Portuguese priest Francisco de Pina, along with priests António de Fontes, Gaspar do Amaral, António Barbosa, and Alexandre de Rhodes. Additionally, there were contributions from Vietnamese and Japanese individuals who helped the missionaries learn Vietnamese. Alexandre de Rhodes played a crucial role in synthesising the work of his predecessors and publishing the Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary, which included a brief grammar of the language of Đàng Ngoài (Northern Vietnam).

The French occupation of Cochinchina marked the beginning of Quốc Ngữ’s popularisation beyond the church’s confines. The Sino-Vietnamese education system officially ended in 1919 with the last Hương examination held in Annam (Central Vietnam). From this point, Quốc Ngữ education expanded nationwide. Vietnamese scholars quickly recognised the utility of Quốc Ngữ in disseminating culture and contributed to its widespread promotion, with Trương Vĩnh Ký arguably leading the way. His translation and compilation works significantly contributed to the development and promotion of Quốc Ngữ. Since 1945, Quốc Ngữ has become the official national script.

VIII. References

AUROUSSEAU Léonard. (1924). Sur le nom de Cochinchine. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrème-Orient, XXIV(3–4), 563–579.

BONIFACY. (1931). Relation de la nouvelle mission au royaume de la Cochinchine (Traduction et annotation du Lieut.- Col. BONIFACY ). Bulletin Des Amis Du Vieux Hué, No 3-4, 279–402.

BÙI Thị Minh Thùy. (2021). Từ điển Việt–Bồ–La và các cứ liệu liên quan. Nhà Xuất Bản Tôn Giáo.

CADIÈRE Léopold. (1931). Lettre du Père Gaspar LUIS sur la Concincina (annotations par L. Cadière). Bulletin Des Amis Du Vieux Hué, No 3-4, 409–432.

CAROLINO Luís Miguel. (2007). Cristoforo Borri and the epistemological status of mathematics in seventeenth-century Portugal. Historia Mathematica, 34(2), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hm.2006.05.002

de LACROIX Antoine. (1631). Relation de la nouvelle mission des pères de la compagnie de Jésus au royaume de la Cochinchine. Jean Hardy Imprimeur & Libraire.

de RHODES Alexandre. (1653). Divers voyages et missions du P. Alexandre de Rhodes en la Chine & autres royaumes de l’Orient, avec son retour en Europe par la Perse & l’Armenie. Imprimeur ordinaire du Roy & de la Reyne (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8607026z/f5.item).

ĐỖ Quang Chính. (1972). Lịch Sử Chữ Quốc Ngữ. Tủ Sách Ra Khơi, Saigon.

ĐỖ Quang Chính. (2011, June 1). Tu sĩ Dòng Tên Alexandre de Rhodes từ trần. Trang Nhà Của Dòng Tên Việt Nam, Tỉnh Dòng Phanxicô Xaviê. Truy Cập Ngày 19/03/2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20191207012251/https://dongten.net/2011/06/01/tu-si-dong-ten-alexandre-de-rhodes-tu-tran/

FUKUDA Yasuo. (2016, March 15). Người Nhật có liên quan sâu sắc tới quá trình thiết lập phiên âm tiếng Việt bằng ký tự Latin. Trần Đức Anh Sơn’s Cultural History and Scholarship Blog (Truy Cập Ngày 5 Tháng 4 Năm 2025). https://anhsontranduc.wordpress.com/2016/03/15/nguoi-nhat-co-lien-quan-sau-sac-toi-qua-trinh-thiet-lap-phien-am-tieng-viet-bang-ky-tu-latin-%e3%83%99%e3%83%88%e3%83%8a%e3%83%a0%e8%aa%9e%e3%83%ad%e3%83%bc%e3%83%9e%e5%ad%97%e8%a1%a8%e8%a8%98/

GAUDIO Andrew. (2019). A Translation of the Linguae Annamiticae seu Tunchinensis brevis declaratio. Journal of Vietnamese Studies, 14(3), 79–114.

HOÀNG Xuân Hãn. (1959). Một vài văn-kiện bằng quốc-âm tàng-trữ ở Âu-châu. Đại Học (Tạp Chí Nghiên Cứu Viện Đại Học Huế), 10, 108–119.

HUỲNH Văn Mỹ, & BẢO Trung. (2014, April 21). Đâu là ‘chiếc nôi’ chữ quốc ngữ? . Báo Tuổi Trẻ Online. https://tuoitre.vn/ky-cuoi-dau-la-chiec-noi-chu-quoc-ngu-603691.htm (Truy cập ngày 29.4.2025)

JACQUES Roland. (1995). L’oeuvre de quelques pionniers portugais dans le domaine de la linguistique vietnamienne jusqu’en 1650 [Mémoire de Diplôme d’Études Approfondies]. INALCO.

JACQUES Roland. (1998). Le Portugal et la romanisation de la langue vietnamienne. Faut-il réécrire l’histoire? Revue Française d’histoire d’outre-Mer, 85(318), 21–54.

JACQUES Roland. (2002). Portuguese Pioneers of Vietnamese Linguistics Prior to 1650 (Pionniers portugais de la linguistique vietnamienne). Orchid Press, Bangkok.

LÊ Ngọc Trụ. (1961). Chữ quốc ngữ từ thế kỷ XVII đến cuối thế kỷ XIX. Việt Nam Khảo Cổ Tập San, 192–193.

Ministère de la Marine et des Colonies. (1865). Revue maritime et coloniale (Mai 1865). https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k34724g/f1.item

NGUYỄN Khắc Xuyên. (1959). Chung quanh vấn đề thành lập chữ quốc ngữ. Văn Hóa Nguyệt San, 39, 167–177.

NGUYỄN Khắc Xuyên. (1960). Chung quanh vấn đề chữ quốc ngữ: Chữ quốc ngữ vào năm 1645. Văn Hóa Nguyệt San, 48, 1–14.

NGUYỄN Văn Trung. (2014). Hồ sơ về Lục Châu Học. Nhà Xuất bản Trẻ.

O’NEILL Charles E., & DOMÍNGUEZ Joaquín M. (Eds.). (2001). Diccionario Histórico de la Compañía de Jesús: Biográfico-Temático. Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu.

PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly. (2018). La gramatisation du vietnamien (1615-1919): histoire des grammaires et de l’écriture romanisée du vietnamien [Thèse de doctorat en Sciences du langage]. Université Sorbonne Nouvelle.

PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly. (2022). Histoire de l’écriture romanisée du vietnamien (1615-1919). Les Indes savantes.

PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly. (2024). Lịch Sử Chữ Quốc Ngữ (1615–1919). Công ty Sách Omega Việt Nam.

PHAN Khoang. (1969). Việt Sử: Xứ Đàng Trong 1588–1777. Cuộc nam tiến của dân tộc Việt Nam. Nhà sách Khai Trí, Saigon.

PINKERTON John. (1811). A general collection of the best and most interesting VOYAGES and TRAVELS in all parts of the world (Vol. 9, pp. 772–828). Longman.

THANH LÃNG. (1961). Những chặng đường của chữ viết quốc ngữ. Tạp Chí Đại Học, Viện Đại học Huế, Số 1, Tháng 2, 6–36.

THANH LÃNG, HOÀNG Xuân Việt, & ĐỖ Quang Chính. (1991). Từ điển Annam–Lusitan–La Tinh (Alexandre de Rhodes). Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội Tp Hồ Chí Minh.

VÕ Đình Đệ. (2022, September 27). Nước Mặn – Nơi có duyên nợ với Đức Cha Lambert. Hội Đồng Giám Mục Việt Nam. https://hdgmvietnam.com/chi-tiet/nuoc-man-noi-co-duyen-no-voi-duc-cha-lambert-46548

VÕ Long Tê. (1965). Lịch sử Văn học Công giáo Việt Nam (Vol. 1). Nhà Xuất Bản Tư Duy Sài Gòn.

VOA Tiếng Việt. (2017). Nhà thờ Phước Kiều, nơi được xem là cái nôi của chữ quốc ngữ [Video recording]. https://www.voatiengviet.com/a/4160976.html (Truy cập ngày 29.04.2025.)

WILBER M. Jason. (2014). Transcription and Translation of a Yearly Letter from 1619 Found in the Japonica Sinica 71 from the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu [Master of Arts Thesis]. Brigham Young University.

[1] INALCO: Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales, National Institute for Oriental Languages and Civilisations.

[2] João Rodriguez is also known by the names João Rodrigues, João Roiz, Joam Roiz Giram (O’NEILL Charles E. & DOMÍNGUEZ Joaquín M., 2001; PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2018).

[3] In the 16th–17th centuries, Macao (under Portuguese rule) served as the headquarter for the Japan Province of the Jesuit Order. As a result, the Jesuits in both Dai Viet (Vietnam) and China reported directly to Macao, as they were subordinate to the Japan Province.

[4] According to Võ Long Tê (VÕ Long Tê, 1965, p. 90), the Portuguese cleric Gaspar de Santa Cruz of the Dominican Order was the first person to preach in Đại Việt. This occurred in 1550 in Hà Tiên, although this territory was not yet officially part of Đại Việt at that time. Additionally, also during the 16th century, missionaries from the Franciscan Order (founded by Saint Francis) arrived in Đàng Ngoài to have an audience with the Mạc Lord, but no missionary activities were recorded (PHẠM Thị Kiều Ly, 2024, p. 78).

[5] Đỗ Quang Chính relied on the following documents to record the biography of F. de Pina: 1) Antonio de Fontes, Annua da Misam de Annam, written in Faifo (Hội An) on 1st January 1626; 2) D. Bartoli, Dell’ Historia della Compagnia di Giesu, la Cina, Terza Parte, Roma, 1663.

[6] Nước Mặn is a town located north of Qui Nhơn, approximately 20km away. It is now part of Phước Quang commune, Tuy Phước district, Bình Định province.

[7] According to Bonifacy’s note in (BONIFACY, 1931, page 286), Thanh Chiêm, Kẻ Chàm, and Ca Chàm are variations of the terms Cổ Chàm or Cổ Chiêm. These terms refer to the ancient land of Champa. Thanh Chiêm is located about 7 km west of Hội An and is now part of Điện Bàn district, Quảng Nam province.

[8] There are many documents available online on this topic. We are citing the following document from Tuổi Trẻ newspaper, accessed on 20th March 2025: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mrQnoyyau80 or https://tuoitre.vn/video/di-tim-loi-giai-cho-bi-mat-mo-co-o-nha-tho-phuoc-kieu-60356.htm.

[9] Older documents state he was born in 1591, but new research indicates he was born in 1593 (Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandre_de_Rhodes, accessed on 19th March 2025).

[10] In Italian, the consonant “c” is pronounced like “k” when it comes before the vowel “a”. However, when it precedes the vowel “i”, it is pronounced like “ch”.

[11] When we were young, we learned that many Vietnamese words originated from French. For example, the word “xà bông” (soap) came from the French word “savon”. At the time, we wondered why the “v” sound in French transformed into a “b” in Vietnamese. Later, we discovered that in Portuguese, soap is written as “sabão”, which is pronounced very similarly to “xà bông”. Readers can explore this further using Google Translate or any translation tool.

[12] The former sites of the Adran school are now Võ Trường Toản High School and Trưng Vương High School in Saigon.

[13] Thi Hương, literraly translated as Regional Examination, was a competitive exam organised every three years as the first part of the imperial examination system in feudal Vietnam to select talented scholars. Candidates who passed this exam were called Cử Nhân (Bachelor) or Tú Tài (Baccalaureate), depending on their grade. The Cử Nhân were eligible for the next-level exam the following year, Thi Hội (Metropolitan Exam held at the capital) and Thi Đình (Palace Exam held in the Palace). Those who passed these two final exams were called Tiến Sĩ (Doctor).

[14] According to Nguyễn Văn Trung (NGUYỄN Văn Trung, 2014, pages 398–399), in 1960, the Đuốc Nhà Nam newspaper in Saigon published an article by Ngọa Long. This article quoted a statement by Đào Trinh Nhất, claiming that during the reign of King Minh Mạng, Vietnamese people in Thailand had published a newspaper in Quốc Ngữ. If this were true, it would be the first newspaper ever published in Quốc Ngữ. However, Ngọa Long unfortunately did not specify in which newspaper Đào Trinh Nhất wrote about this, and Đào Trinh Nhất also did not provide the source for his observation. Nguyễn Văn Trung stated that he could not find any trace of the alleged newspaper.

[15] Readers can find the works of Trương Vĩnh Ký on the website of Hội Ái Hữu Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký –Úc Châu (Petrus Truong Vinh Ky Alumni, Australia, Incorporated) (https://petruskyaus.net/petrus-ky-tac-pham/).